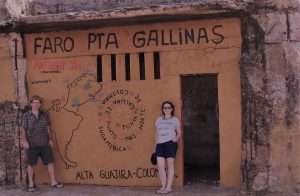

Few places in South America have poverty like the far-northern desert wastelands of Colombia. La Guajira is Colombia’s most northerly region and a marked contrast to the prosperous green lands of the central coffee region where we spent Christmas. It’s wild, remote, windy and inhospitable up there. But at the top sits our Holy Grail destination, the most northerly point of the whole South American continent: Punta Gallinas. On our South American journey so far, we’ve visited the most southerly, easterly, westerly and the geodesic centre points of the continent. It would be churlish to leave without popping up to see Mr Northerly. En-route we have the challenge of driving the mud-pan pie-crust and the dilemma of the poverty-stricken Wayuu children (click here for Map and notes for self-drive to Punta Gallinas).

Where the Guajira is that?

So… La Guajira. Ever heard of it before? You have now! At the very top of South America there’s a sticky-up bit, a peninsula reaching into the Caribbean. It’s mostly Colombian territory, but a teeny sliver down the east side is Venezuela. The indigenous Wayuu people are proud that they have never in history been conquered, not even by the Spanish. Given the godforsaken, inhospitable nature of the place, I have a teeny suspicion that the colonisers just maybe didn’t put up much of fight for this patch. But full credit to the indomitable Wayuus, they have historically held this ground well and continue to do so. The Wayuu refuse to answer to the authorities of Bogota and continue their subsistence lifestyle in a state of somewhat lawless semi-independence.

For much of the year the terrain is arid, rough, scrub desert. In the short rainy-season it floods, turning the access tracks into quagmires and the vast salty-mud-pans into treacherously soft swamps. As the rain clouds wander away, a pie-crust coating of sand forms on the surface of the swamps. Under the pie-crust lie thick, slimey mud-pools which just could, should it be foolish enough to stray onto it, swallow an Iveco Daily 4×4 whole. Well… okay, ‘swallow whole’ might be a slight exaggeration, but it would at least get very quickly bogged beyond the axles. We’re keen not to test this.

Local Hero

Winching a coach

Before pushing-on with the potentially hazardous schlepp over the pie-crust to Punta Gallinas, we do what the cool kids call ‘hanging out’ for a couple of days in the back-packer/kite-surfers’ spot – Cabo de la Vela. Reaching this far is a relatively easy drive, but it’s still a wee-bit of a rough dirt-road to get there. Certainly not ideal for the snazzy 50-seater air-con coaches that take Colombian day-trippers out there. One might expect that having the cojones to drive 50 tourists to a dirt-road location, the driver might have checked-out which tracks his coach could take which weren’t suitable, but it seems… No! Sure enough, after we have winched a Bogota family Landcruiser from an ill-advised mud-route near the village, we’re asked to help with a huge coach that had sunk his rear axle.

A grateful coach crew

We hesitated, wondering whether Cuthbert and his trusty winch would manage to pull such a large vehicle. But bless his little soul, with chocks under his front wheels to stop him dragging himself towards the bus, Cuthbert tugged and heaved, finally extracting the coach. Big cheers from the attendant passengers who stood around, wasting hours of their precious holiday time, watching the rescue.

Following the Dusters

Anyway… it’s time to tackle our Holy Grail destination of Punta Gallinas! Wallace, our GPS, offered a myriad of potential routes across the mud-pans, but remember that pie-crust-thing we mentioned? Our worry was not finding just a route, but finding a route with a pie-crust strong enough to take Cuthbert’s six tons. Tricky.

Duster convoy

As we’re leaving Cabo de la Vela at early o’clock, we see a load of Colombian Renault Dusters gathering. 43 of them in fact. And they’re all adorned with ‘Expedition Punta Gallinas’ stickers. Hmmm… interesting. We stop for a chat. They’re setting out in convoy across the pie-crust too! Turns out, they’re just as interested in Cuthbert and his rough-road capabilities as we are in their route to Punta Gallinas. They’re a friendly bunch and happy for us to join them.

Now… these Renault Dusters aren’t the most capable rough-road vehicles in the world, but they are 4×4 and well kitted-out with expedition-type gear: jerrycans, hi-lift jacks, sand-ladders and all the Gucci gear. But even loaded-up as they are, they are nowhere near as heavy as Cuthbert. We follow them super-cautiously out onto the pie-crust, watching carefully so see how much of an indent their tyres make into the surface. It’s nerve wracking, but at least it’s a super-smooth drive.

There’s about 30-40 km of mud pie-crust to cross before reaching the final stage of rocky terrain. From here we have no worries. There are no more mud-pans and the route is relatively straightforward on the GPS. The Dusters’ limited ground clearance means they take it frustratingly slowly through rocky sections that Cuthbert handles with ease and speed. They feel guilty holding us up, so we go on ahead without them and enjoy the afternoon at Punta Gallinas.

Eventually as it’s getting dark, we’re settling down for the evening when the Duster convoy comes rolling in. One of them is carrying his entire front bumper and faring on his roof-rack, and all of them look totally whacked and exhausted. It has taken them almost six hours to do the final 25km stage of rocks and deep-sand that Cuthbert did in around 40 mins. Eeiiishhh!!!

Wayuu Kids

So that’s how we dealt with the dilemma of crossing the mud pie-crust. But this drive, and indeed the whole Guajira peninsula, presents another challenge: dealing with the Wayuu kids. La Guajira reminds us very much of parts of Africa: the terrain, the heat and the poverty. These kids have nothing. Well… nothing except the generosity of the passing visitors to the area, a resource which they have been trained by their parents to exploit with some degree of success. From the very tiniest of tots, they are taught to stand at the side of the track and beg. Some simply stand there with their hands out, but many more have adopted another trick: holding a piece of string across the track. Their theory is that drivers should stop and offer goodies in exchange for passage.

So… here’s the dilemma… should we succumb and encourage super-cute tiny-tots to beg at the side of the road?

At the first string ‘barrier’, some of the cars in the Duster convoy ahead of us, give out sweets. We give out some small packets of wholemeal biscuits (I know… not exactly ‘health food’, but far better than boiled sweets). Others in the convoy drive gently but decisively towards the rope, making it clear that they have no intention of stopping and at the last second, the kids drop their rope.

So the first ‘barrier’ is done, but soon comes another ‘barrier’. And another. And another. For several kilometres it’s relentless. The further we go, the more frequent the ‘barriers’ become. In some places, they’re literally just three or four metres apart. We have over a hundred kilometres to go to Punta Gallinas and simply don’t have enough biscuits to feed every Wayuu child in La Guajira!

We decide to ration the biscuits by giving to those ignored by the convoy cars in front of us. The kids are all very good natured and smile/wave even when we drive through their ‘barriers’ without giving. We notice that some of them have arms full of every conceivable type of the cheapest, stickiest candy, and this we find to be part of our dilemma. If indeed it is right to respond to children roadside begging (and we’re not convinced that it is), surely it cannot be right to stuff the poor kids full of sugar? But let’s just say, for arguments sake, that it is okay to dish-out tooth-rotting candies of minimal nutritional value to children begging at the side of the road, should it be done selectively? Or to every single one? And if it’s done selectively, how to select which child? Anywhere in the world, the look of disappointment on the face of a child who another sees another child get candy, tugs at the heartstrings.

We find it all very disconcerting for a while, but soon realise that these kids only beg on the first part of the route, the part passed by visitors heading to a ferry trip. Once we pass the point where most visitor turn north to catch the boat, we can enjoy a ‘dilemma-free’ drive for most of the way to Punta Gallinas.

We manage to save some biscuits to give out on the return journey, but again, it’s simply not possible to feed them all and we’re forced to make random decisions of which to give to and which to drive through. We stopped for a chat and a laugh with some of the slightly older ones. They explained that there is a school where they “learn lots of things”, but few of them seem to attend. Their cute faces are no doubt more valuable to their parents when collecting whatever they can get at the side of the road, rather than learning to read and write in a classroom.

Waiting for the Dusters – Punta Gallinas

Obviously, we have no idea what the answer is here. We can’t speak with any authority and have no understanding of the ‘real’ story. It’s no doubt a complex socio-political issue with great historical and cultural sensitivities. But we understand anecdotally that the Wayuu’s demand for a large element of autonomy from the Colombian government is leading to their community not receiving central funding.

The Wayuu tell us that they reject all police presence out there and that as an indigenous people, they’re entitled to make their own laws and rules. But this is an arid, sandy, unfeasibly hot and inhospitable land. We see little evidence of the Wayuu’s ability to support themselves. Their livelihood appears to depend on organised child begging rackets, supplemented by selling old Coke bottles filled with contraband petrol smuggled over the border from Venezuela. If the children receive no education other than to stand by the track and beg for sweets (a very shot-lived career, fading rapidly when they lose the super-cuteness of extreme youth) the future isn’t looking bright for this community.

We did it!

We made it!

For us, the highlight of this excursion into La Guajira is reaching the hallowed Punta Gallinas. After the south, east, west and centre points of the continent, we are truly thrilled to round off our two year South American trip here at the far north. When we heard about the mud pie-crust route palaver, it disappointed us greatly to think that Cuthbert might be too heavy to get us here. But thanks to 43 Renault Dusters escorting us gallantly across the mud-pans, we not only made it safely here, but we gathered a GPS track to follow meticulously back across the pie-crust!

On arrival back to ‘civilisation’ we received confirmation that Cuthbert’s shipping is now booked to move on to Panama in just three weeks. Exciting times! 😊

Route Map and Notes for Self-driving to Punta Gallinas

If after reading the story, you want to do the drive to Punta Gallinas yourself, we’ve added below a detailed map of our track (zoom in and scroll around) and some notes for the route.

Conditions: important to check at the time. The route can be wholly impassable in the rainy season. Even getting to Cabo de la Vela can be tough in the wet; the whole area turns into a swamp. There is a police check-point at the cross-road where you turn north off the ruta 90, and another check-point in Uribia, so you can ask them about the prevailing conditions. The tarmac stops at Uribia and it’s a good gravel road for around 50 km until the turn-off to Cabo de la Vela. From there it’s rough dirt and depends very much on how much rain there has been.

Provided it’s not too wet and you stay on the main tracks, the drive to Cabo de la Vela can be done in any car. From Cabo to Punta Gallinas, a 4×4 isn’t strictly necessary, but there is a bit of sand in the final section so 4×4 would be an advantage. High-clearance is more essential. The track is a little bit rough in parts and there are some rocky sections towards the end of the route.

What to take: Make sure you have the fuel range and plenty of water and food for the trip. It’s hot, dry and remote, no filling stations or shops out there. Best to be self-sufficient, however, there are a couple of hostals with restaurants when you get to the Punta Gallinas area.

Routing: Our map shows the way we went (starting from the turning off the main gravel road), but don’t follow it blindly over the mud-pan sections. The routes across the pans change every year after the water has dried. Check which way the locals and the tour trucks are taking – use the tracks which look the most driven. If in doubt – don’t go onto the mud pans until you are happy. The tour Landcruisers take back-packers out there almost every day when the route is accessible. They leave just after dawn, so you can look out for them and follow them for the first section of the route (if you can keep up with them). Importantly though, they do not go all the way to Punta Gallinas by land. They turn north up the western side of the bay (the inland section of sea that sits immediately south of Punta Gallinas) and tourists go by boat across the tiny stretch of water to the Punta Gallinas peninsula. They then continue the rest of the way to Punta Gallinas by other vehicles. To drive all the way there, you need to route around the south to of the bay/inland sea and head up the eastern side, past the Taroa beach (see route map).

Timing: depending on how your vehicle copes with the terrain and provided you don’t make too many wrong turns, it should take 4-5 hours from Cabo de la Vela.

Roadblocks: These are obviously flexible. How many you encounter and what you are asked for will depend from day to day. At one or two they will accept nothing but money (just 1,000 or 2,000 pesos per car), but at most of them, the kids just want sweets. With hindsight, we wish we had taken some pens, pencils and kids books to hand-out instead of biscuits. It’s a personal decision, but please don’t let these put you off going. It’s great trip and we never felt unsafe or threatened at any time – just give what you think is right and gently drive through the kids’ string barriers where you don’t want to give. We did this for several and the kids all dropped the rope, smiled and waved.