February 2015

So, for the rather longwinded reasons explained back in The Visa Problem, we find ourselves back at the Plumtree border-post, exiting Zimbabwe for Botswana. We headed down to Francistown for a night-stop and to raid an ATM for some Pula currency. And to plan… what next??

So, for the rather longwinded reasons explained back in The Visa Problem, we find ourselves back at the Plumtree border-post, exiting Zimbabwe for Botswana. We headed down to Francistown for a night-stop and to raid an ATM for some Pula currency. And to plan… what next??

It is now a couple of months since we did any ‘critter spotting’; in fact our last game-drive was back in Kenya at Christmas. Botswana is famous for not much other than its safaris and game parks, so where better to look for a spot of safari-time? We scoured the maps and found the Khama Rhino Game Park near Serowe, some 2-3 hrs drive to the south of us. Off we go then!

Incidentally… this is meant to be the ‘rainy season’ on this side of Africa, but we haven’t seen much of the wet stuff since northern Malawi over a month ago!

Khama Rhino turned out to be a great decision. We had a lovely couple of days there and were spectacularly successful with the rhino spotting. We have only seen three rhino in Africa so far, so we were chuffed to see so many in just a couple of days in the park. And the park was so quiet! On the first day there was just one other vehicle in park, and on day two, we seemed to have the whole park to ourselves 🙂 . As we have mentioned before, we very much appreciate Cuthbert’s facilities when we are on safari (see Multi-tasking in the Kalahari). First, we sit so high in the cab that we can see over all the bushes that obscure the view for ‘ordinary’ 4x4s. Secondly, we can park-up at a good game viewing spot, climb into the living cab and have a cup of tea, lunch etc., all whilst watching and taking photos of the rhinos drinking at the waterhole! We have even been known to wake-up and drive out of the campsite in our pyjamas, ready to have our morning cuppa and breakfast watching the sun coming up over a herd of buffalo at a waterhole 🙂 . Marvellous!

It is a sad state of affairs that because the park hosts one of the largest rhino populations in Africa, security has to be extremely tight. Poaching is a problem all over Africa: killing elephants for their ivory is a famous example, but it seems to us that the rhino problem is even more serious. Obviously we don’t condone the poaching of any animal, however you don’t have to drive around Africa for long to realise that there are many thousands more elephant on the ground than rhinos. The rhino is the most endangered of the commonly poached species in Africa.

Rhino horn remains in demand in the Middle East (particularly Yemen and Oman) to make dagger handles and in the Far East for ‘alternative’ medicines and aphrodisiac potions. Apparently, in the Far East the demand for rhino horn had started to decline some years ago when successful controls on poaching limited the supply of animals and drove prices up to an unaffordable level. But since the dawn of the new ‘super-rich’ class in China, demand is now rising again and a single rhino horn can allegedly fetch as much as US$ 1 million in China. Another sad fact of the tragic poaching story is that some of the rhino poaching is carried out by the park conservation staff. This is reported to have been a particular problem in Kenya’s parks, where an estimated 30% of all rhino poaching was committed by park staff.

At the Kharma reserve, they have taken two approaches to protecting their rhino: first, they have kept the park very small by African standards. It is therefore easier to monitor the whole park area (unlike Kruger for example, which is so vast that it is much more difficult to contain the poaching problem). Secondly, Kharma has engaged the Botswanan military to carry out the rhino protection. Soldiers patrol the park in vehicles, on foot and on horse-back with the park rangers, to monitor the animal population and to deter any would-be poachers. Sad that they have to go to so much trouble to protect the animals, but what a good idea! And what a great posting to get, if you happen to be in the Botswanan Army!

Click here for more pictures of the amazing game in the Park: Khama Rhino Park Gallery

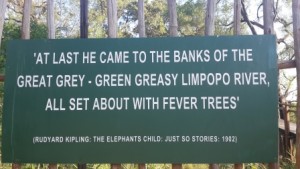

After our wonderful ‘rhino time’, we headed on southwards towards the Limpopo River which forms this part of the border between Botswana and South Africa. On the Botswanan northern shore of the Limpopo River is an area known as the Tuli Block: a strip of land around 300km across and 10-20km deep. This land was ceded by the British South Africa Company to white settlers in the 1800s but proved to be too rocky to cultivate, so was set aside for wildlife.

After our wonderful ‘rhino time’, we headed on southwards towards the Limpopo River which forms this part of the border between Botswana and South Africa. On the Botswanan northern shore of the Limpopo River is an area known as the Tuli Block: a strip of land around 300km across and 10-20km deep. This land was ceded by the British South Africa Company to white settlers in the 1800s but proved to be too rocky to cultivate, so was set aside for wildlife.

Starting at Martin’s Drift at the western end, slowly working our way eastwards, we stopped for a few nights at various camps along the river. This is a pretty rather than spectacular area of scenery, but there is plenty of wildlife around and we enjoyed once again, falling asleep and waking-up to the sound of hippos grunting in the river (thinking back, the last time we had this pleasure was back in Kenya at Lake Naivasha in December) and as we ate our breakfast, watching the crocs swim past down the river hunting for theirs.

By the time we reached the Limpopo at Martin’s Drift and saw South Africa just a short distance across the river, the potential problem of ‘will we/won’t we’ obtain our required visa for South Africa was starting to weigh on our minds. We tried not to let it spoil the week leading up to the ‘Big Border-crossing’, but as we worked our way slowly eastwards towards the ‘target’ Pont Drift crossing out of Botswana, we constantly wondered whether we would soon be travelling back down this same road in few days, in the opposite direction, having failed to obtain our South African visa.

The Limpopo River has several crossings which form border posts between South Africa and Botswana. The most easterly is Pont Drift, but it is marked on the map as only being passable when the river levels are low. Despite it being the ‘rainy season’ the rains do not seem to have materialised in this part of Africa this year, so the water levels are not very high and we decided to head to Pont Drift and give it a try. It is the most remote and therefore likely to be the quietest of all the crossings, but just before we reach that point, there is a geological feature of the Tuli Block that is worth visiting in its own right: Solomon’s Wall.

On approaching Solomon’s Wall we spotted immediately that it is a red ‘dolorite dyke’, created millions of years ago by molten lava pushing up through a weak seam in the earth’s crust – well actually we read it in a book afterwards, but sounds impressive doesn’t it? 🙂 In any case, it is an impressive 40m high natural stone ridge, which is starting to crumble in a way that makes it appear to be a huge disintegrating man-made brick wall. This ridge formed a line across part of what is now the Tuli Block, but at some point in history, a section of the wall was washed away by the Motloutse River, leaving the remaining parts of the Wall extending north and south, either side of the river. The Motloutse River is dry at the moment, so it is easy to descend into the dry river-bed to view the Wall from all angles. It is a curious sight.

After having marvelled at the Wall and taken all the requisite photos, we realised that the road onwards to Pont Drift had collapsed; to climb out of the Motloutse river-bed was looking like a ‘challenge too far’ for Cuthbert. A steep bank, 9 or 10 metres high, of deep, soft silt and sand stood before us. Not only that, but the river bed immediately at the base of the bank (from which Cuthbert would have to start his climb), was extremely wet, soft and sludgy silt. Hmmmm…..

Never quick to be defeated in these things, we decided to give it a go with Cuthbert, but several attempts at climbing the bank were futile – the sand was too deep and soft. We tried to use Cuthbert’s winch attached to a ground-anchor on the top of the slope, but the ground was not firm enough and as we wound in the winch, the anchor just pulled towards us out of the ground. Bearing in mind that we were still in a ‘dangerous critter zone’ with elephant, lion and leopard wandering somewhere in the bushes around us, we were reluctant to spend too much time outside of Cuthbert digging him out of the deep sand-ruts that he was digging himself into. Had Cuthbert been a bit lighter (without full tanks of 230 litres of water and 240 litres of fuel) he might have been able to make a more successful attempt, but today it was not to be! We reversed back down the slope and retraced our steps back the way we had come.

The next morning we set off again for Pont Drift border crossing, this time on a more northerly route where the dry Motloutse is spanned by a bridge. When we reached a gate around 40 km before the Pont Drift crossing, the guard admired Cuthbert and, seeing the elephant logos on the side, asked whether we were here to survey the elephants (this is not an uncommon impression that Cuthbert seems to give – maybe we should give it a try sometime 🙂 ). “No, we’re just heading through to cross at Pont Drift into South Africa” we explained. “No.” came the reply, “People can cross with the cable-car*, but no vehicles…”. Bugger!!! 🙁 [* some kind of a cable car is apparently a unique feature at Pont Drift border crossing, allowing local pedestrians to cross, but no vehicles (although given the number of crocs and hippos in the river below, you would rapidly become a tasty croc-snack if anything went wrong!!)]

Disappointed at having to turn back again, we headed to the next border-post just 50km (ish) along the Limpopo at Platjan Crossing. We were confident that this one was open as we had met some travellers who had crossed there just a couple of days before. We exited Botswana and crossed the low and very narrow bridge (of sorts) across the river to try to enter South Africa.

Now we would see whether we could sweet-talk the Immigration Official into give us the visa that we wanted. Hold your breath and tune in to the Return to South Africa page to find the next thrilling instalment…

Here’s a map of our final Botswana route. Red line = our route on this trip in Cuthbert (see story at Botswana); Blue line = routes travelled on previous trips.